Making a Difference: Image to Action

On May 25th, the International Center of Photography hosted “Making a Difference: Image to Action, Photographer as Activist.” The panel featured members of three contemporary collectives developing visual works and experiences that function outside of gallery walls, beyond the typical borders that maintain art in a pedestal of ambivalence. Demonstrating how photojournalism is operating in social spaces today, principal members of #Dysturb, MTL Collective, and 1in20 shared their experiences with designing direct social actions around the printed and moving image.

The co-founders of #Dysturb opened the panel with a presentation featuring a recent project created in conjunction with the European Parliament, for International Women’s Day, 2016. #Dysturb assembled a series of eleven images by different photographers to raise awareness about women refugees escaping war-torn countries and remapping their lives throughout Europe. These images were wheat pasted throughout European capitals with multi-lingual texts. Kyla Woods was very clear about how #Dysturb functions in society: “We use the street, we use social media, and the other tool we use is education.” By working with schools in the development of participatory projects, students engage with contemporary events, and with each other. “The goal is not to convince someone of something,” said Benjamin Petit.

The way we talk, discuss, and value how visual language permeates our society is a dialogue that moves through many variants and referents. Are we reviewing this language through a discourse of aesthetics? Or through a lens of political efficacy, within contexts of art practices, or even through an economic matrix? Can we even discuss contemporary art through only one of these avenues for analysis? When driven by direct action, art has proven itself as an effective tool for making invisible social forces known and visible. There's a long lineage for framing this form of engagement, a lineage that precedes and overlaps with the images of Riis, Austen, Hine, leading up to the “concerned photographer” ethos that dominated photography in the 1940s and 50s.

People make things because they care about a particular outcome, ethics, or a specific event. Paolo Uccello’s The Battle of San Romano, 1435 structured a visual narrative based on the social tensions between Florence and Siena. Francisco de Goya didn’t paint The Third of May, 1808 under a spell of ambivalence. An advocate for social reform, Honoré Daumier painted The Uprising, 1860 based on a street protest in Paris.1 By the time Martha Walter painted The Telegram, Detention Room, Ellis Island in 1922, 600,000 immigrants had already entered Ellis Island in 1921.

Although paintings remain objects of private domain, it is through circulating media that political engagement continues to be mostly felt. I was thinking of Daumier’s political cartoons for newspapers when Amin Husain of MTL Collective said, “If you look at 2010, public space is being reclaimed, bodies in space. That’s an important political act. And so, our walls are our media. We don’t control mass media, we don’t have access to it, the story is being told to us, but it’s very powerful to have a wall that has a disturbance poster. Everyone takes photos, it self-generates its own media, and on a hashtag [the message] can reach further. The act of transgression of doing something on the wall lets people know that you were there.”

MTL Collective creates multi-lingual publications, public works, and direct actions aimed at institutional reform. On how MTL sees their work, Husain said that although “some people would call them projects, we would think of them as involvements.” Across borders, disciplines and levels of engagement, Husain described the working process of MTL as one of response and engagement rooted in research, and strategically deployed action: “We came back from the West Bank and were watching what was happening in Tunis and Egypt. We identified the areas that had uprisings and found their most circulating newspaper, printed out their front page on 17x11 and translated the headlines, removed the ads and distributed them in public spaces around the city.”

Through actions designed to align individuals with their shared goals, MTL operates outside of traditional art environments, working within systems that shift in real-time at the service of social betterment. Husain added that “at moments like these in history, knowledge is on the ground amongst people, so it’s not about representing, or organizing, or identifying, but hearing, listening and having the conversation among us.”

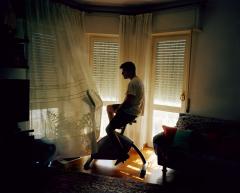

Turning a taboo into a social conversation was the reason Marvi Lacar co-founded 1in20. Lacar's training as a storyteller began with photojournalism: “I wanted to talk about the values that I was passionate about, but through other people and their stories. And then I got sick.” A personal struggle with mental illness led Lacar to use Instagram as a central site for collecting visuals and stories by people also struggling with mental health in their lives. Using the most popular photography online platform, Lacar works to destigmatize discussions around mental health.

For Lacar, photography is the essential tool through which the self can give shape to the interior world. Leveraging the space between the interior world of thought and self-perception, with insight into the real life struggles of invisible states of being, Lacar believes that “photography can really help you understand what you’re going through.” The name for Lacar's collective emerged from a statistic defined by the World Health Organization: for every person who dies of suicide, another 20 will attempt to do so.

The intellectual lineage of making visible the hidden costs and risks of groups under socio-political pressure continues in the work of #Dysturb, MTL Collective, and 1in20. As media landscapes change, perspectives for creative advocacy respond and redesign how social change is accelerated by dialogue enabled by visual and/or experiential information exchange. As we live through the largest human refugee crisis on record, we have no shortage of issues to address. Gathering individuals and resources with the goal of activating forms of transformation is a very accessible method to restore power balances to public and private spaces. The works by these three contemporary collectives also pose a larger question to any art context that avoids these issues: for whom is there a benefit to ambivalence?