Your Mirror: Portraits from the ICP Collection

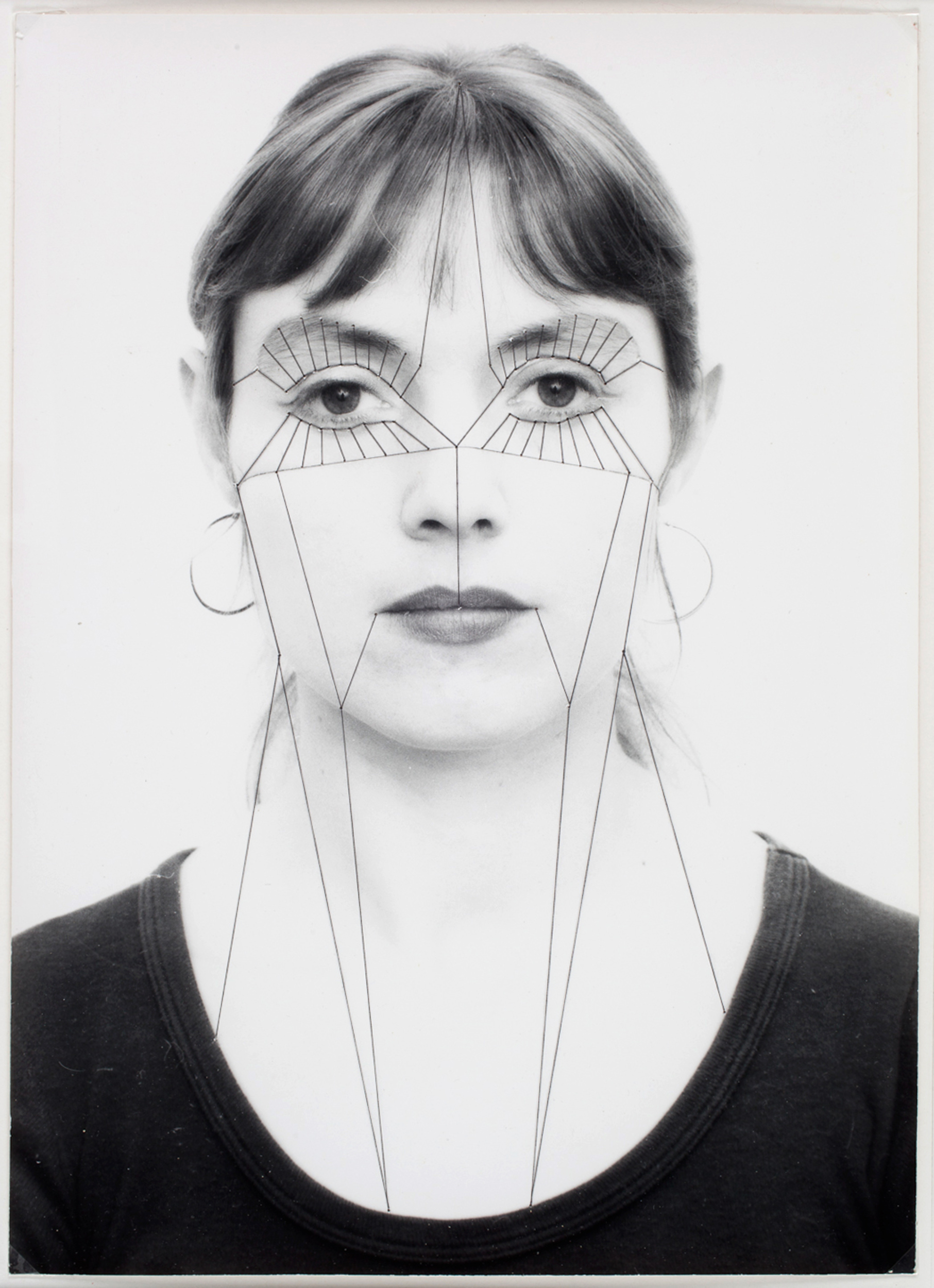

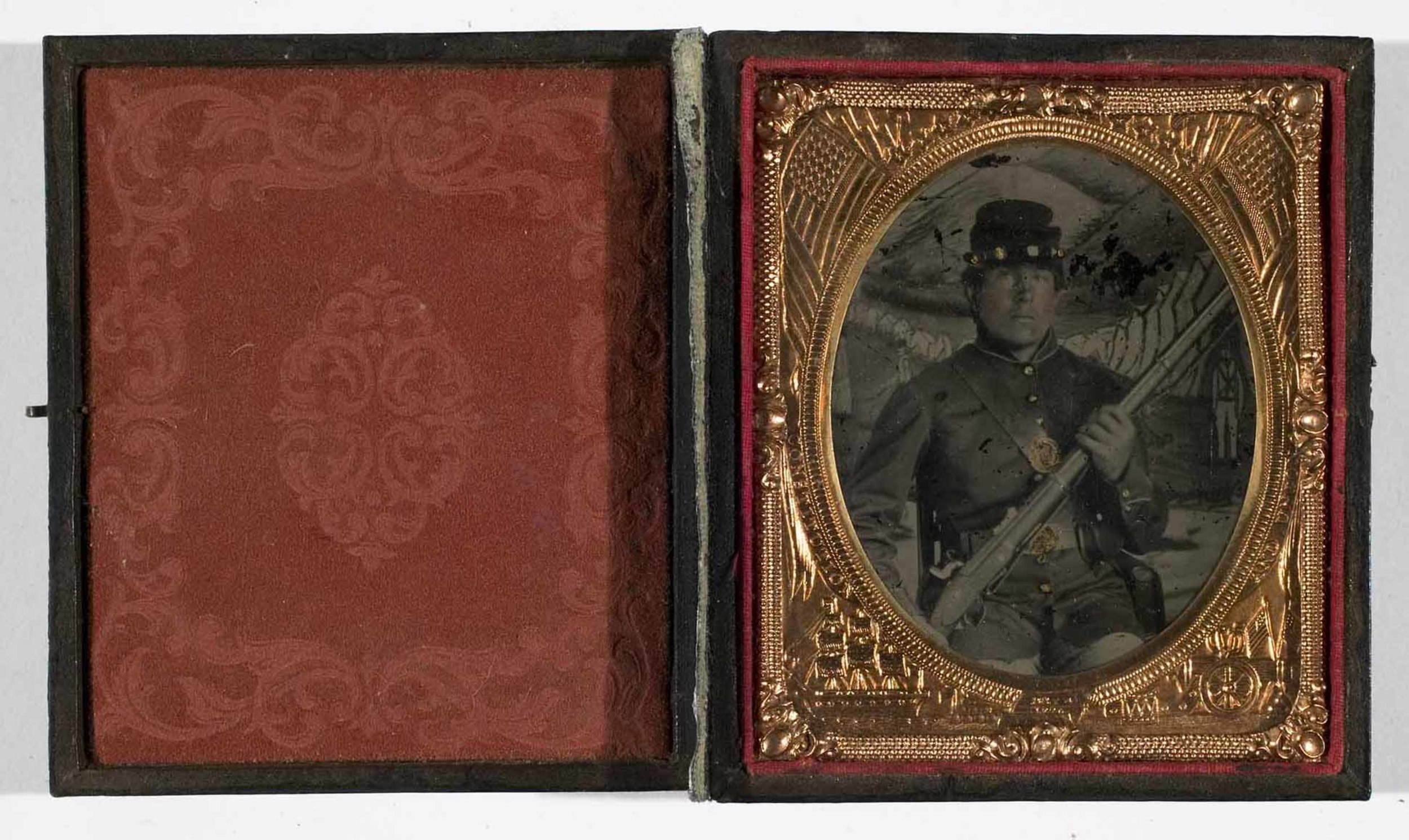

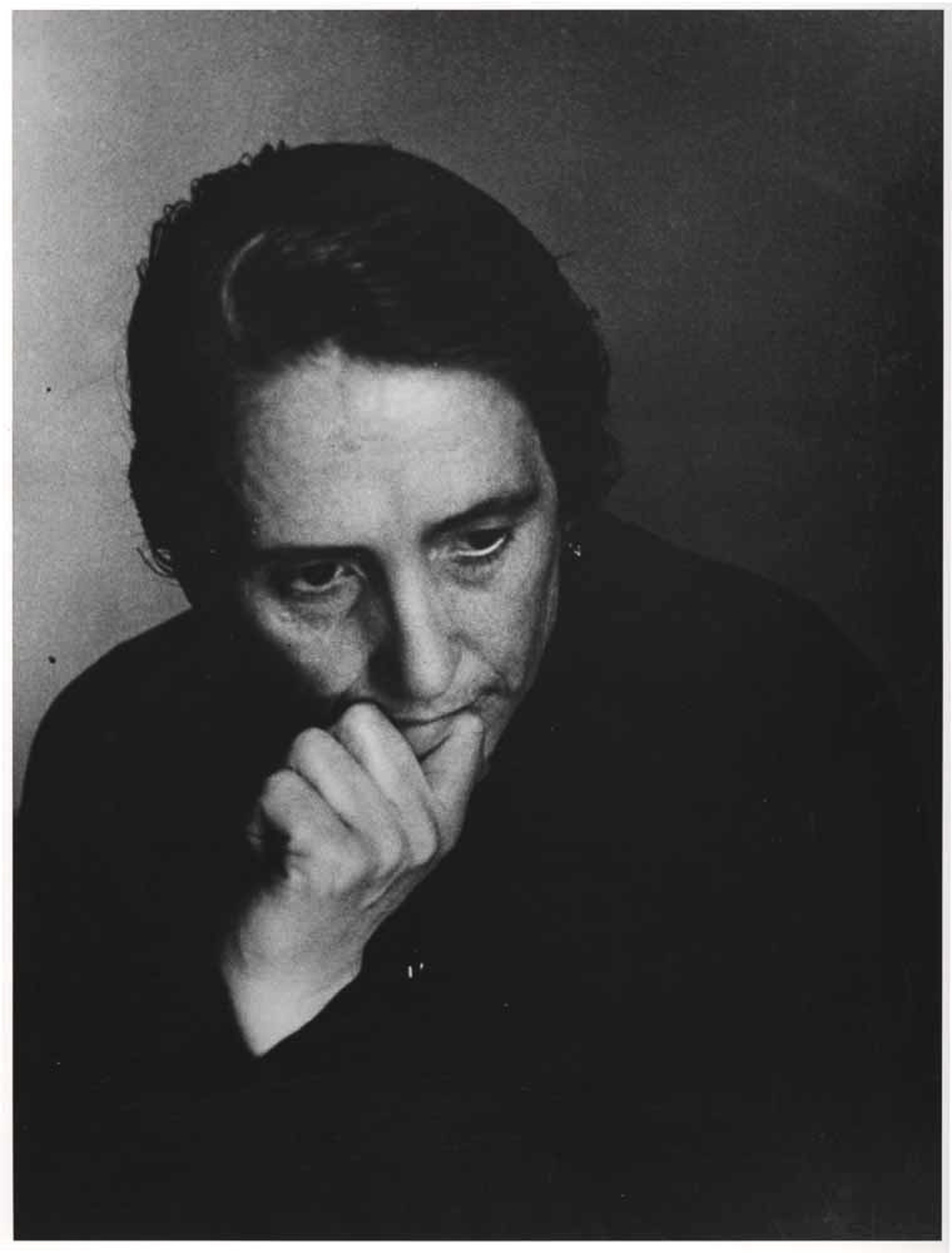

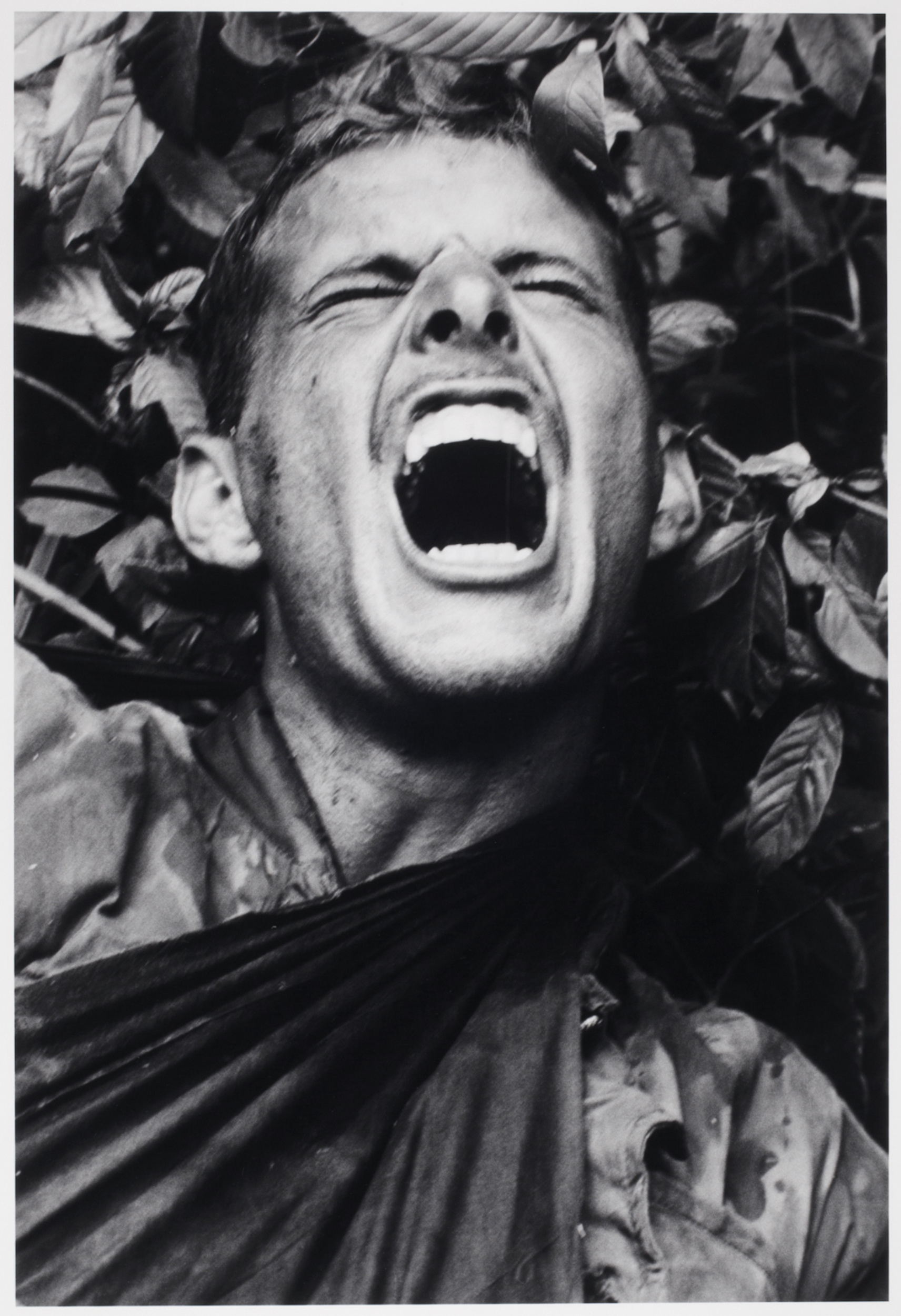

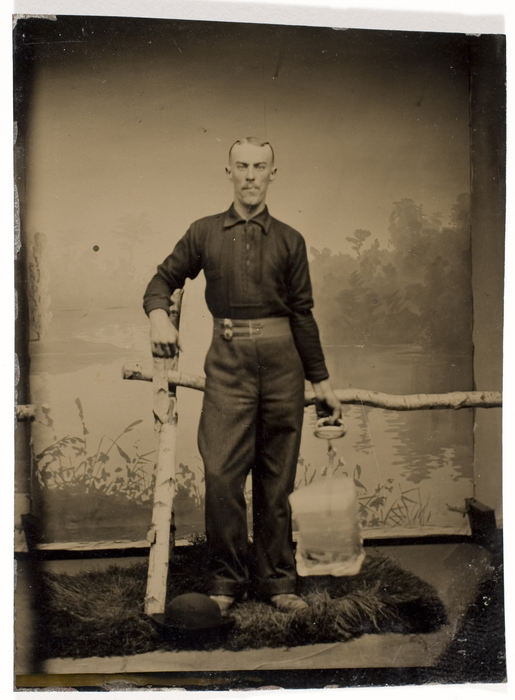

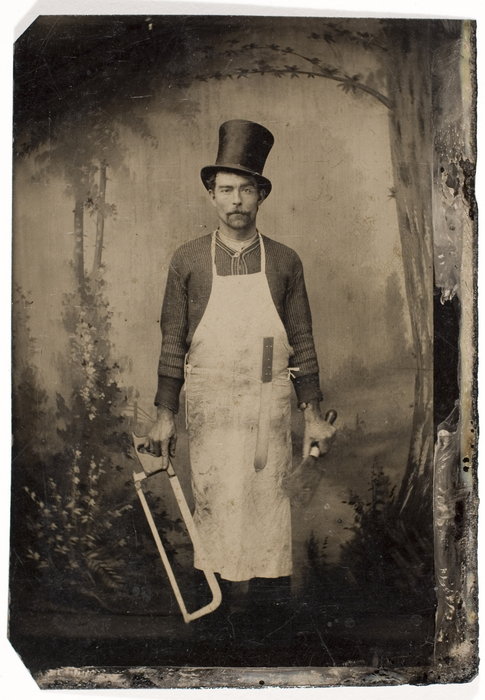

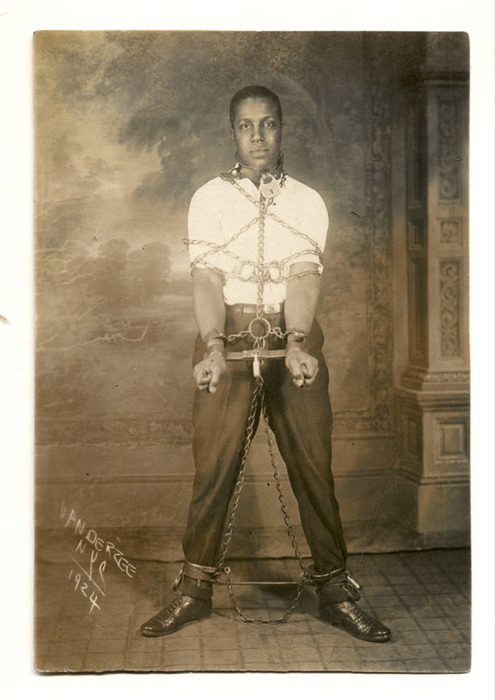

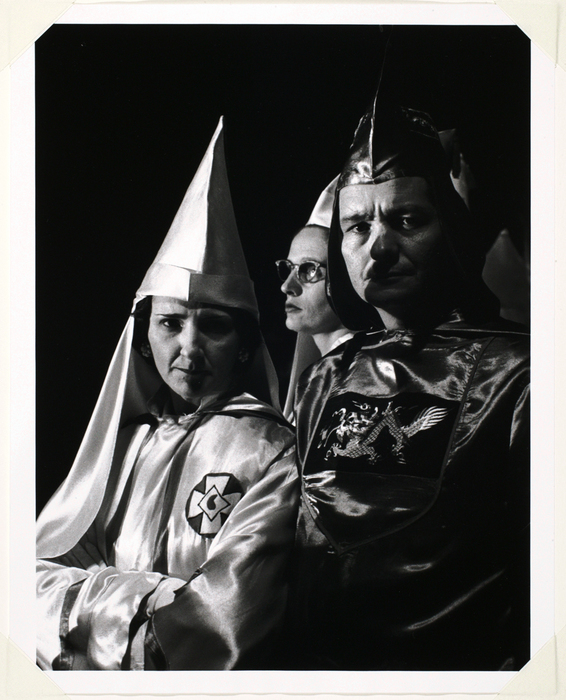

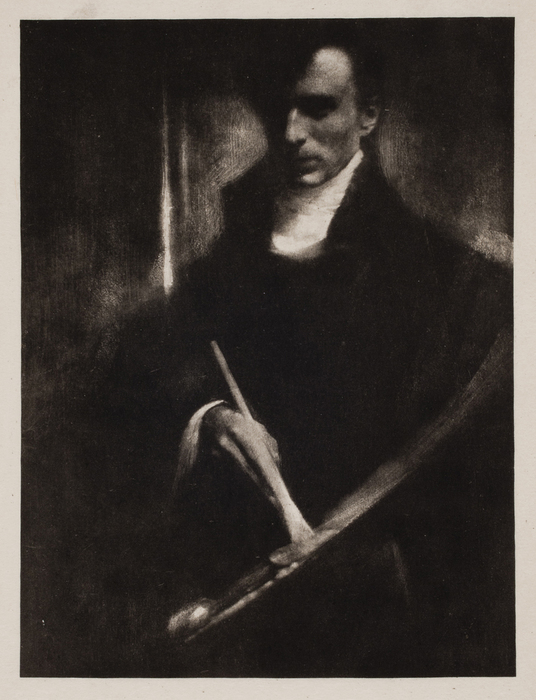

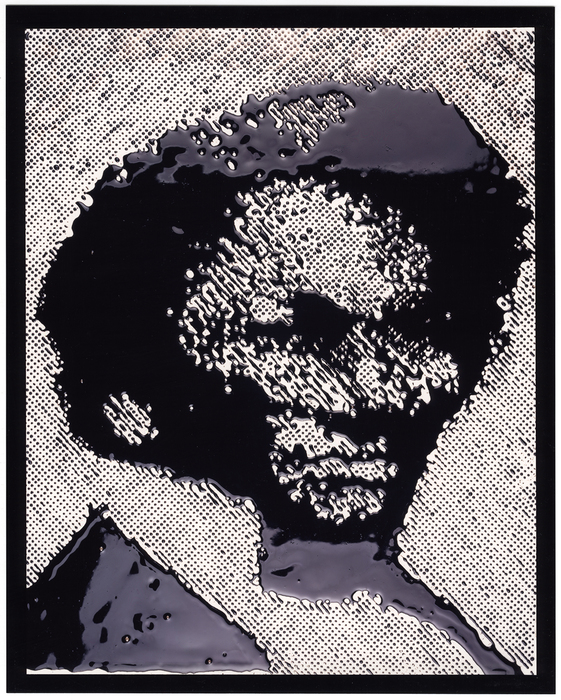

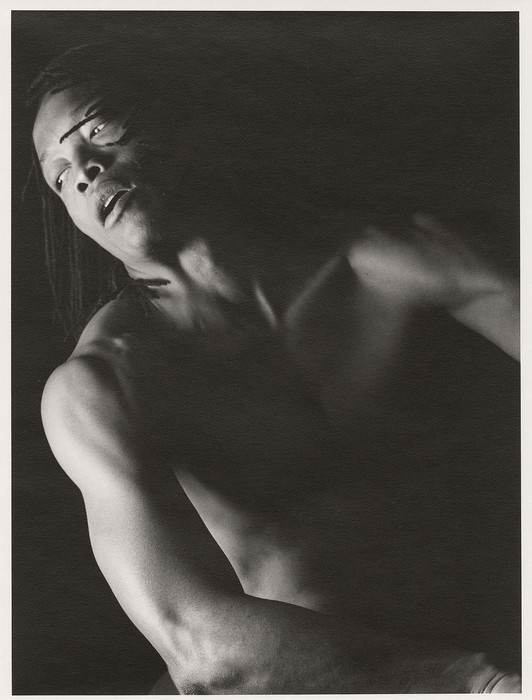

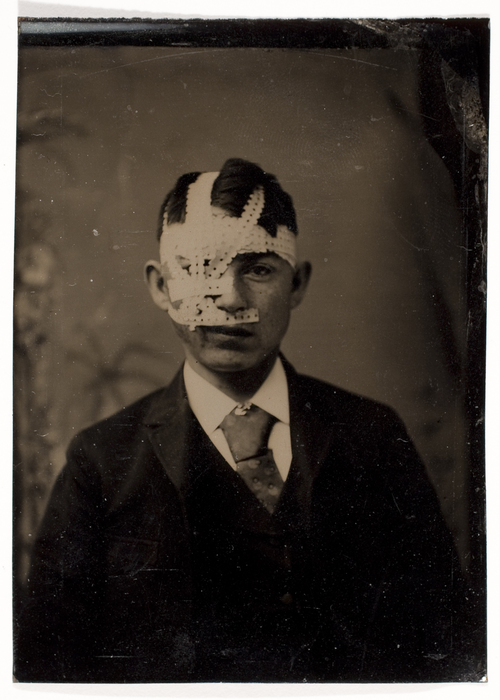

Images that seem to encapsulate individual human identities, from nineteenth-century daguerreotypes to twenty-first-century selfies, have dominated the medium of photography. Portraits shape the ways we understand each other and ourselves. Many crucial aspects of modern political, economic, social, and cultural life are constituted through, not simply documented by, pictures like the ones in this exhibition.

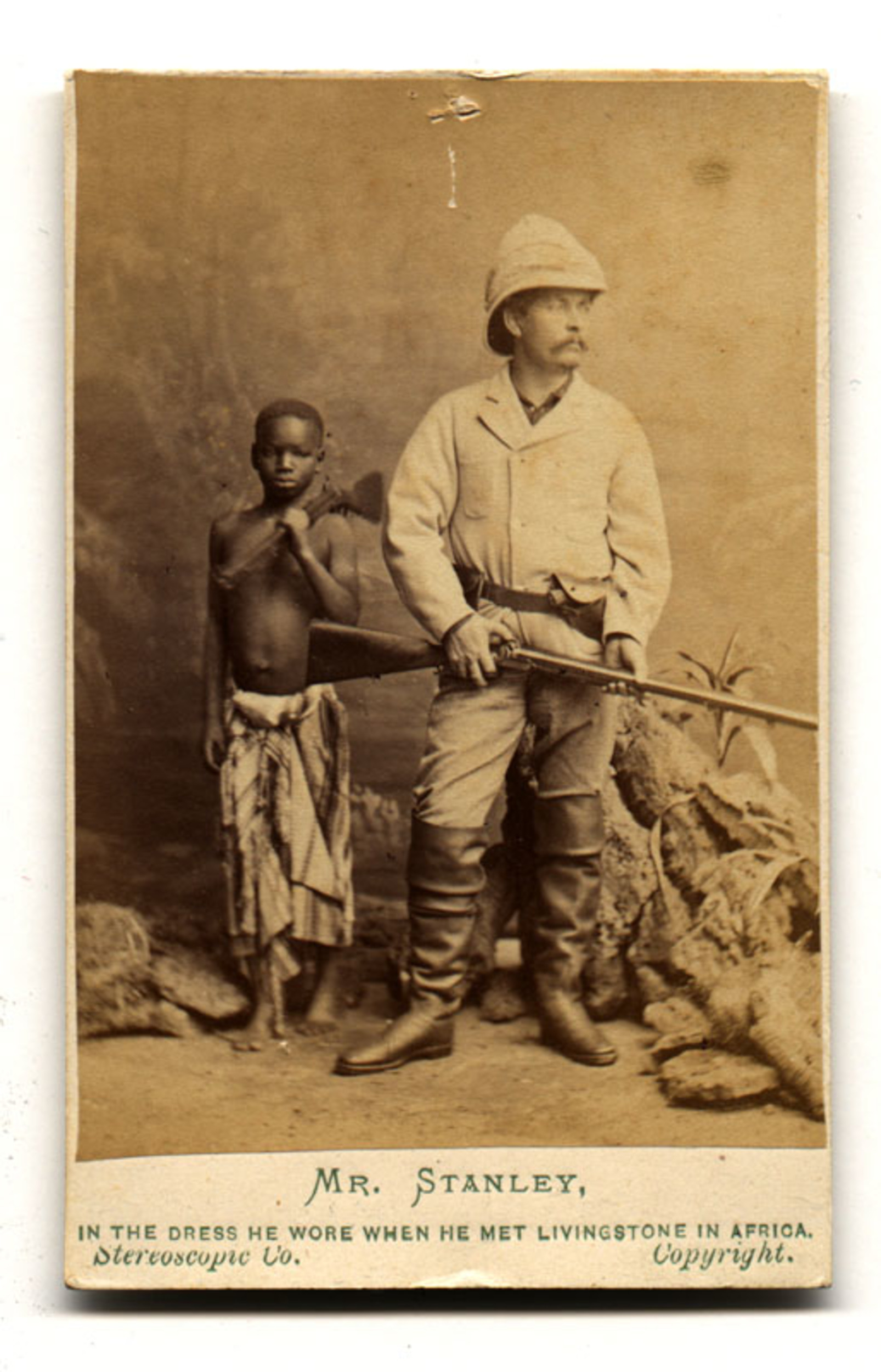

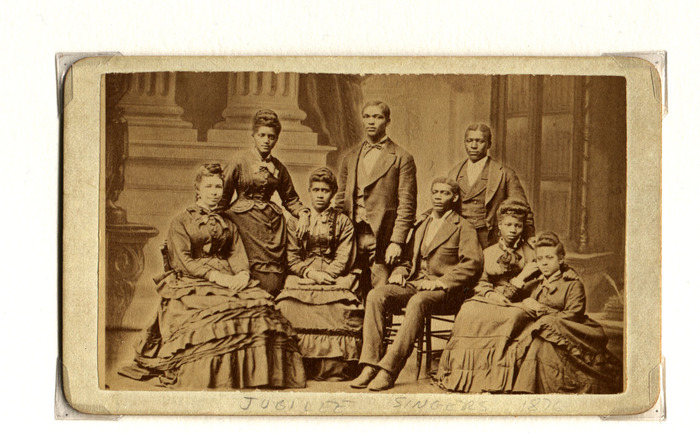

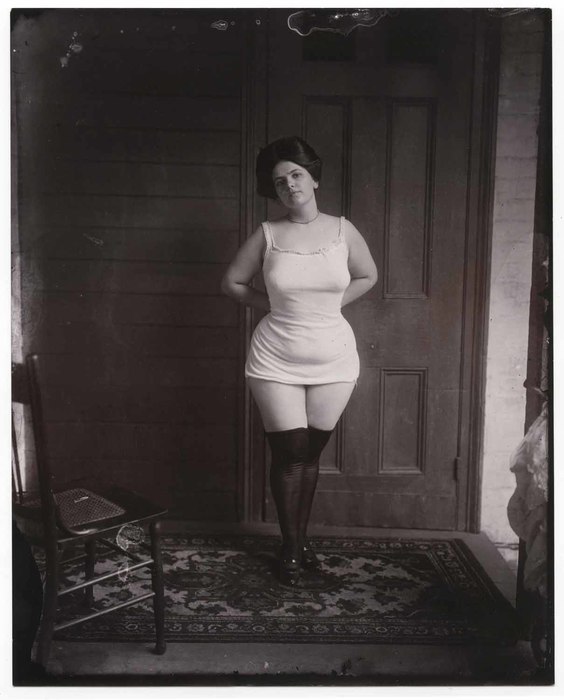

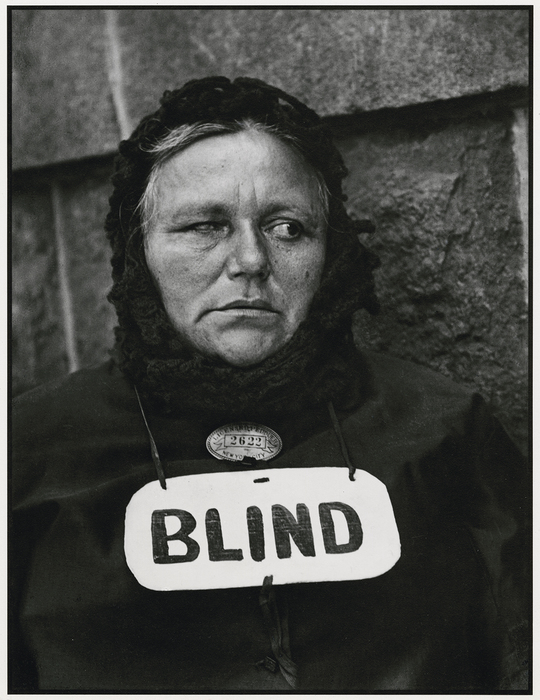

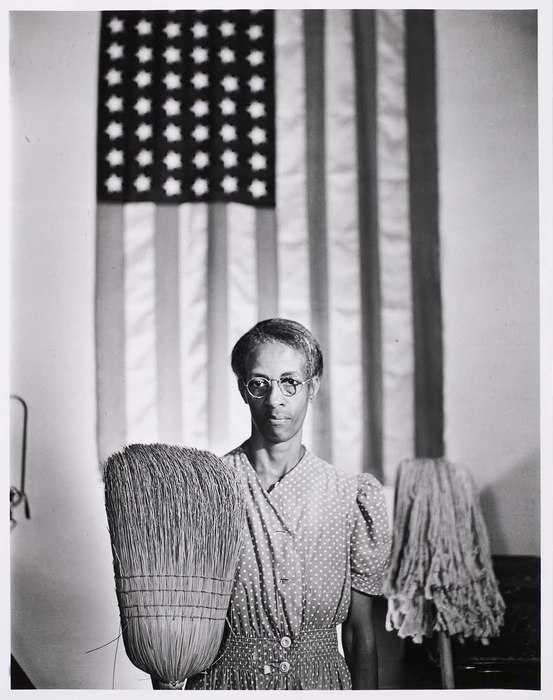

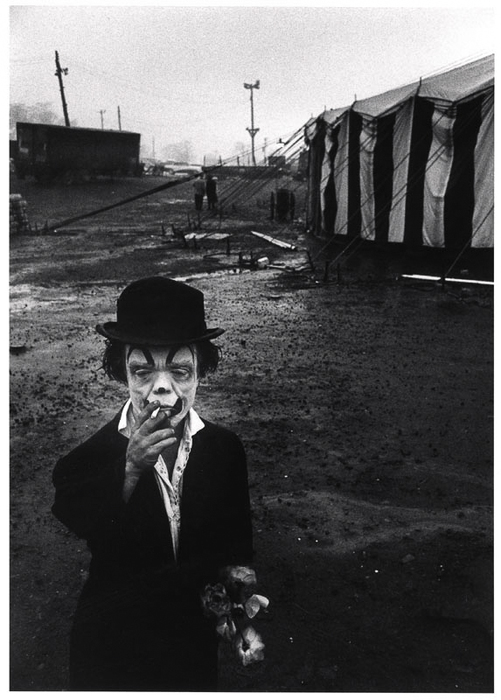

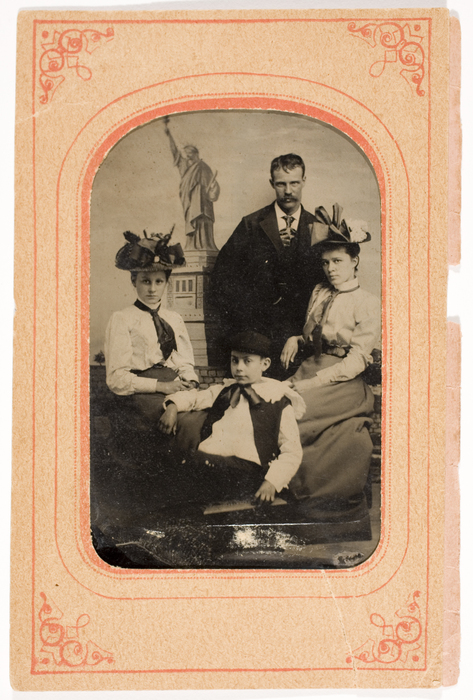

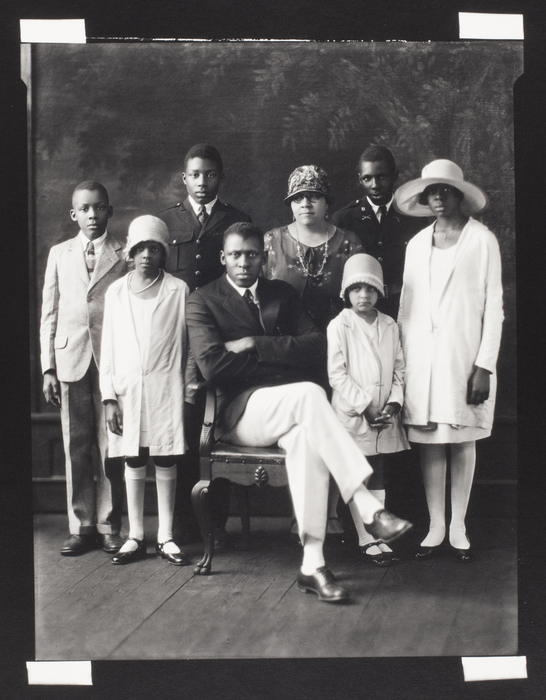

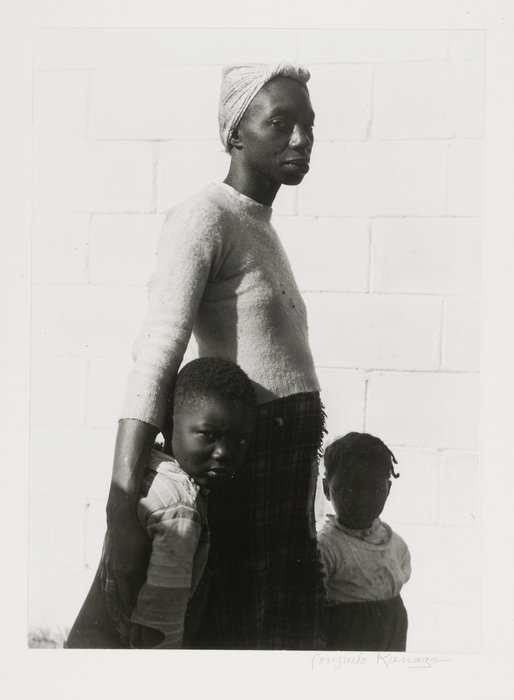

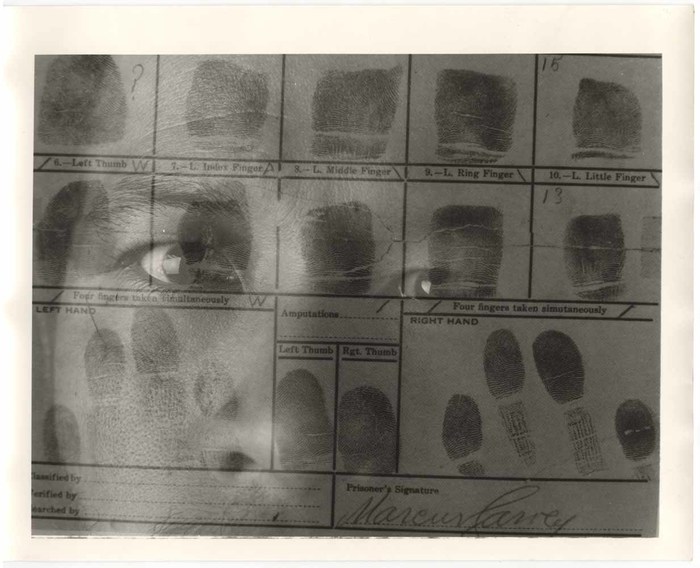

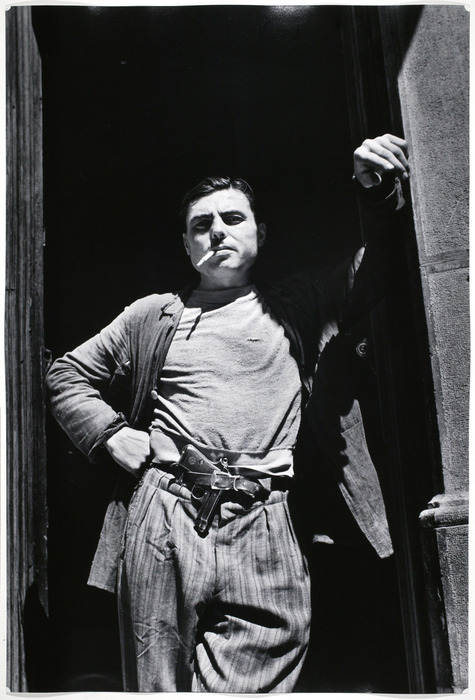

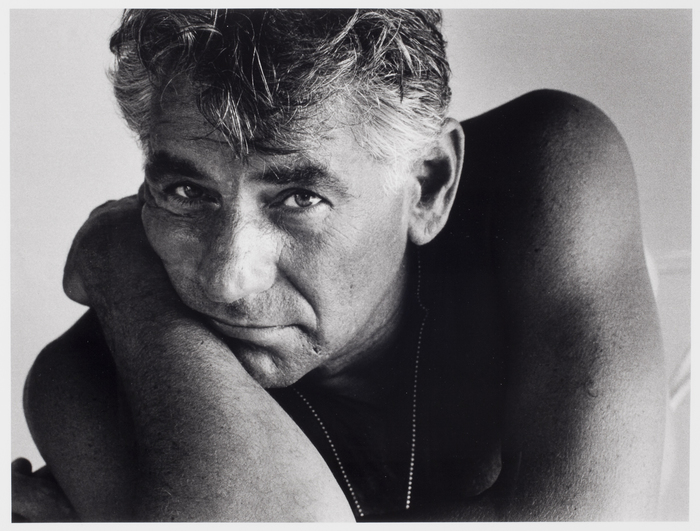

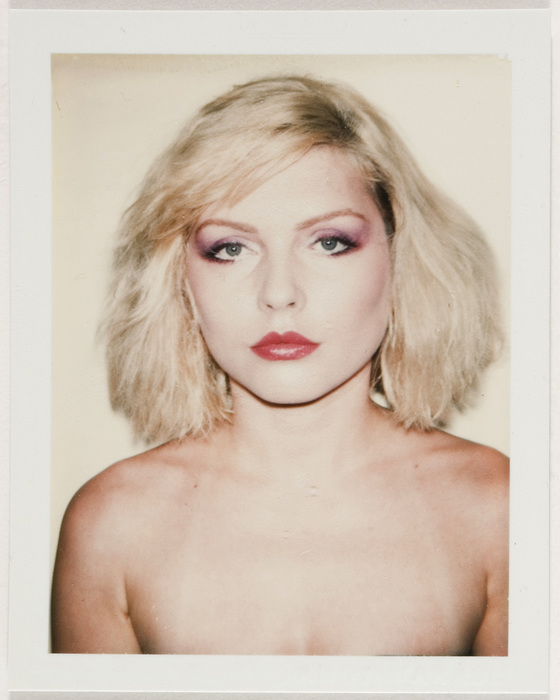

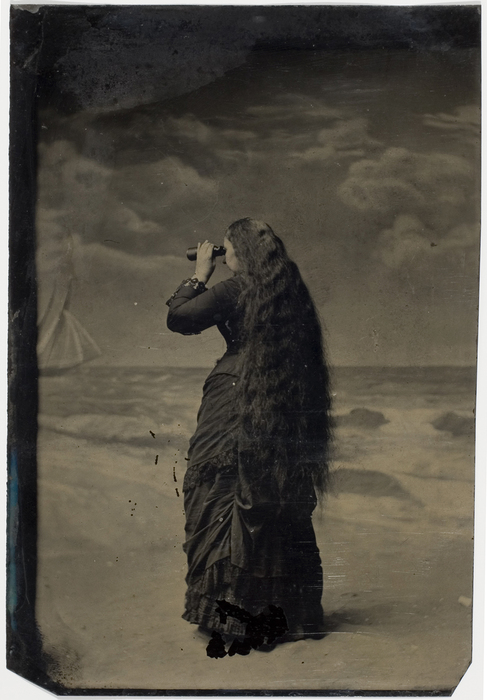

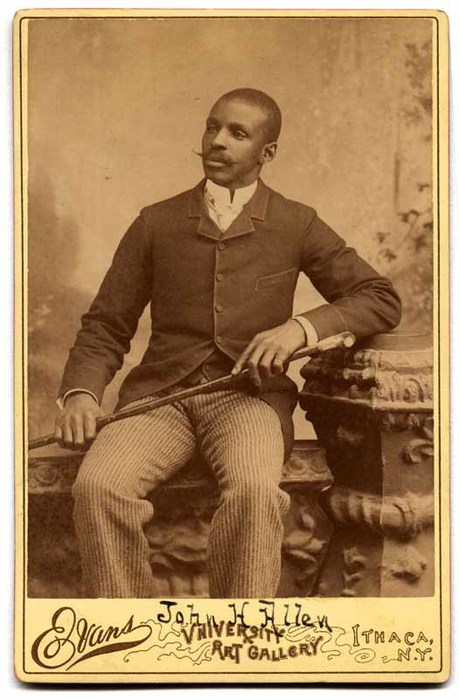

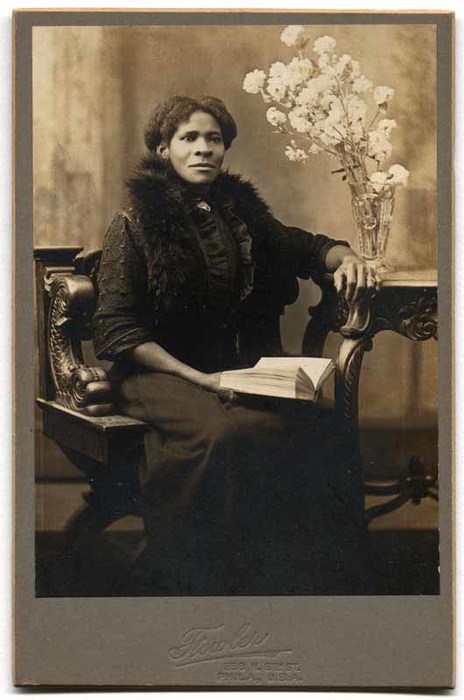

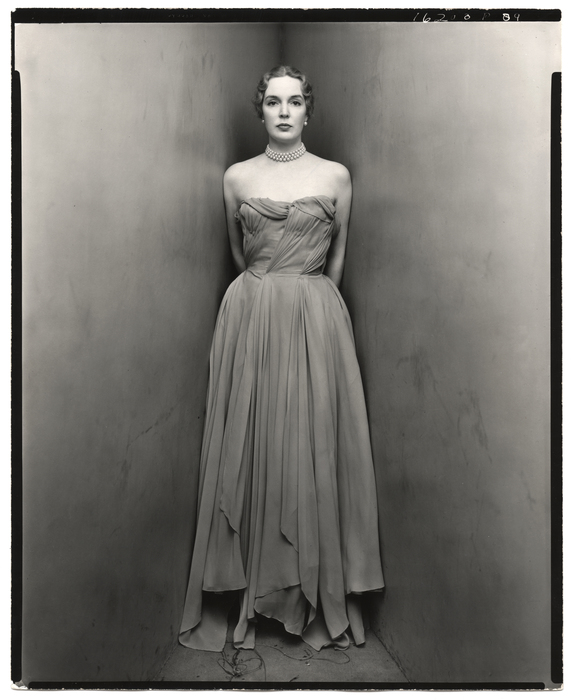

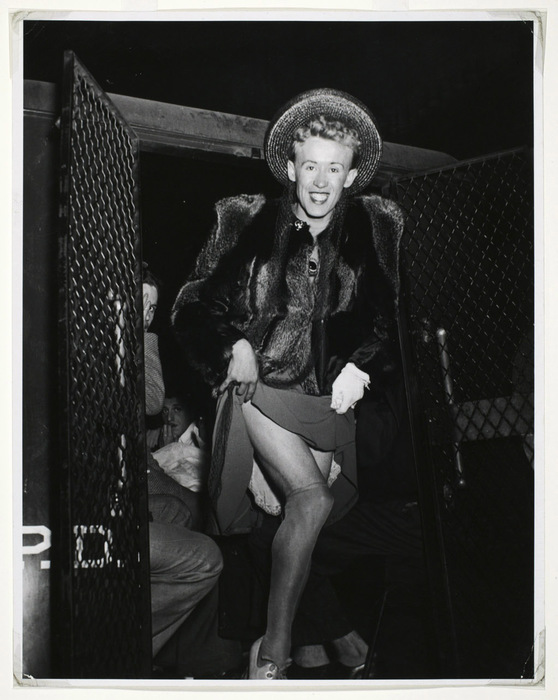

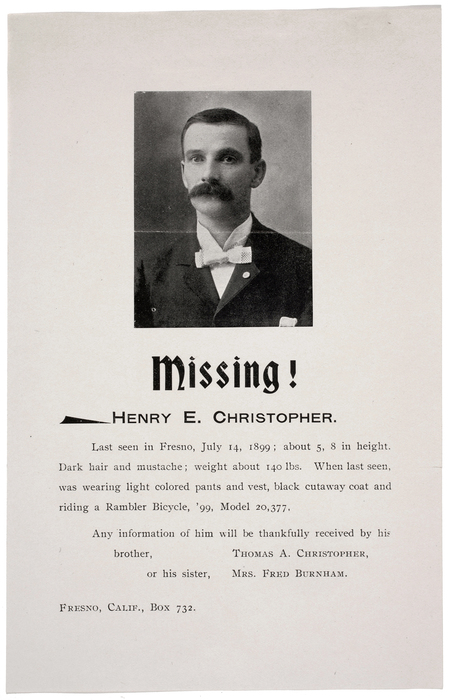

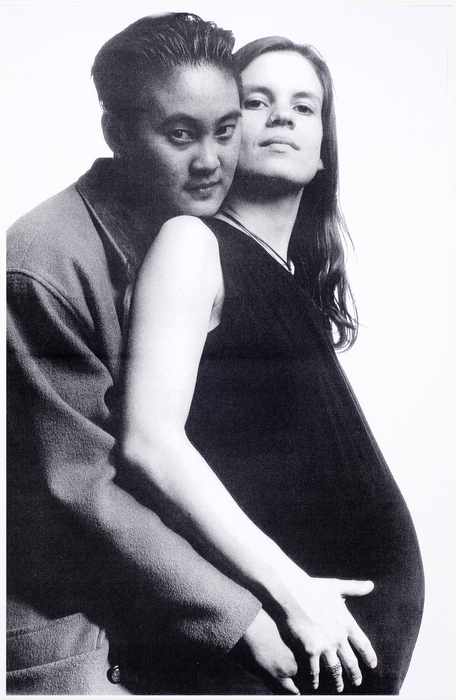

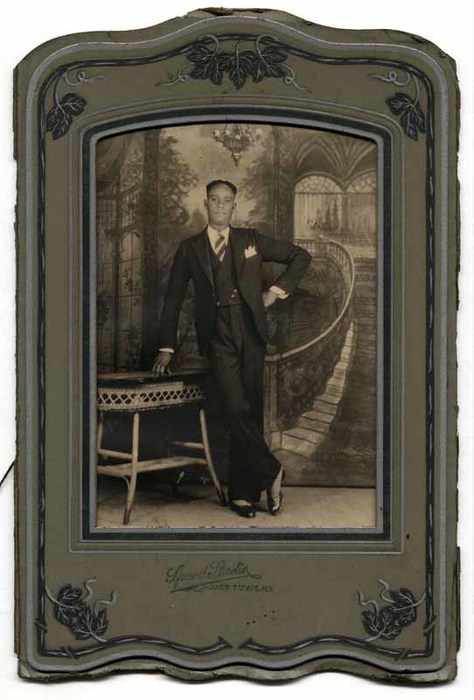

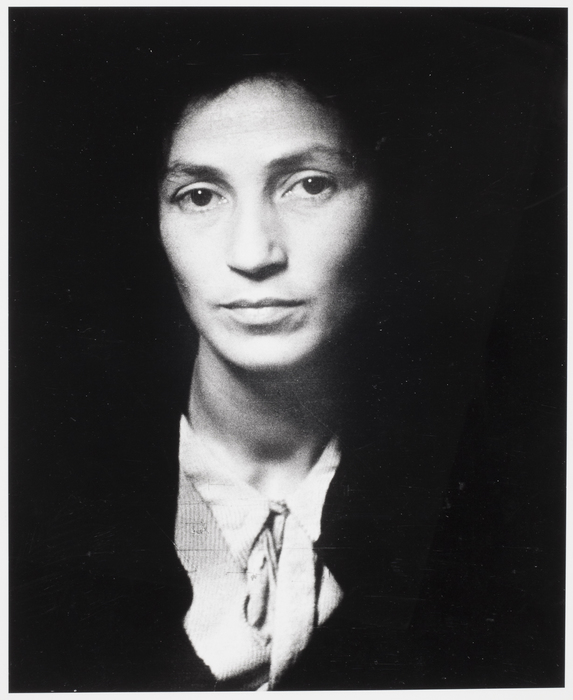

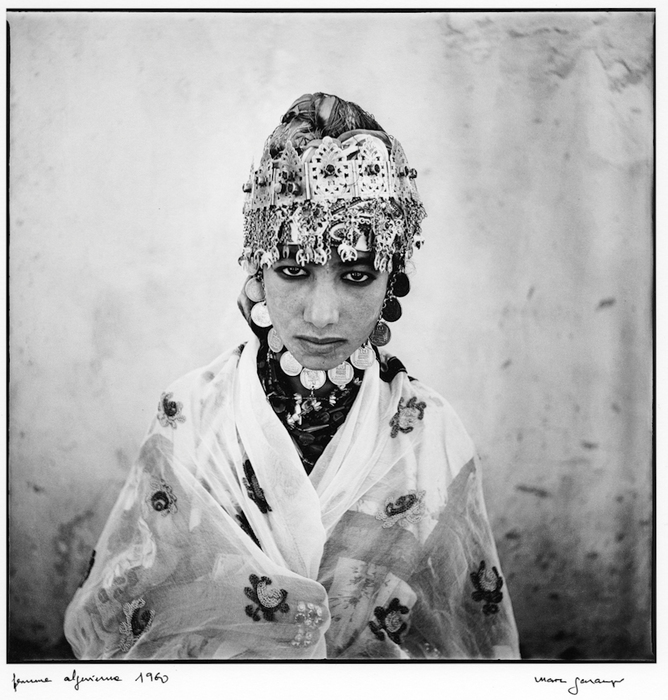

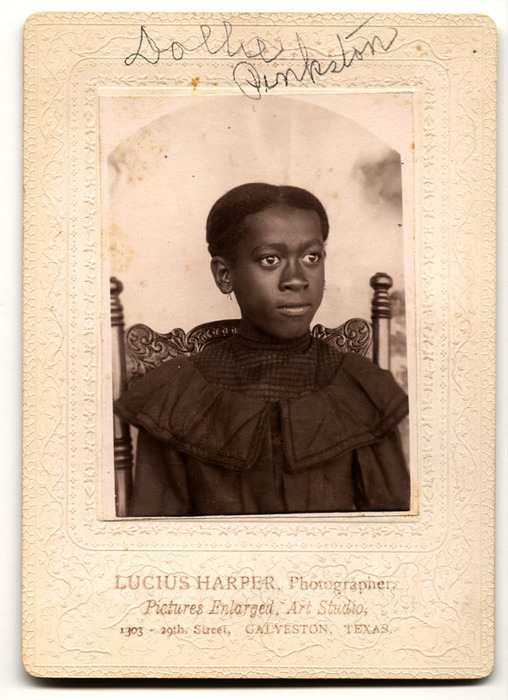

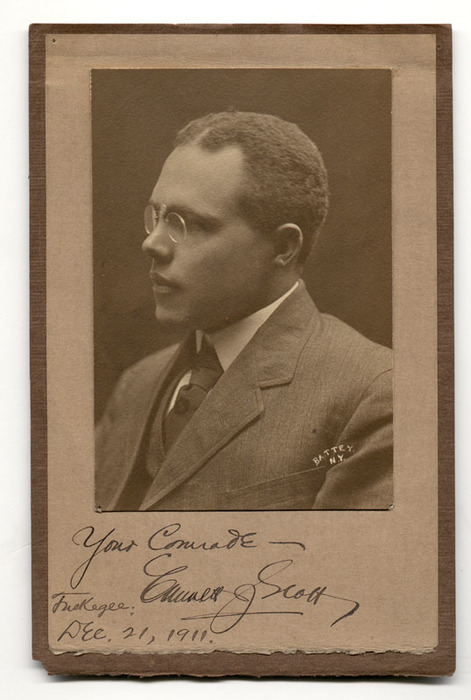

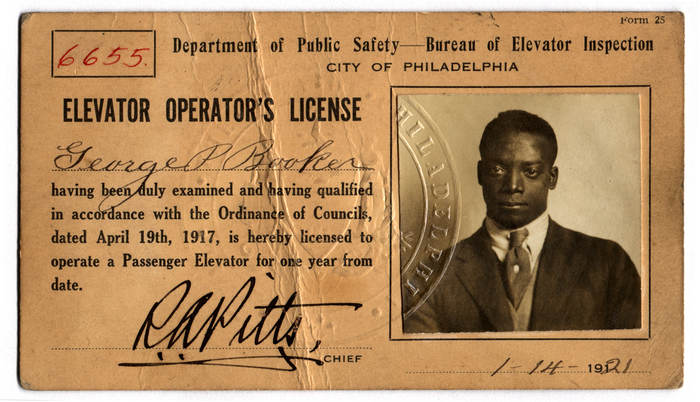

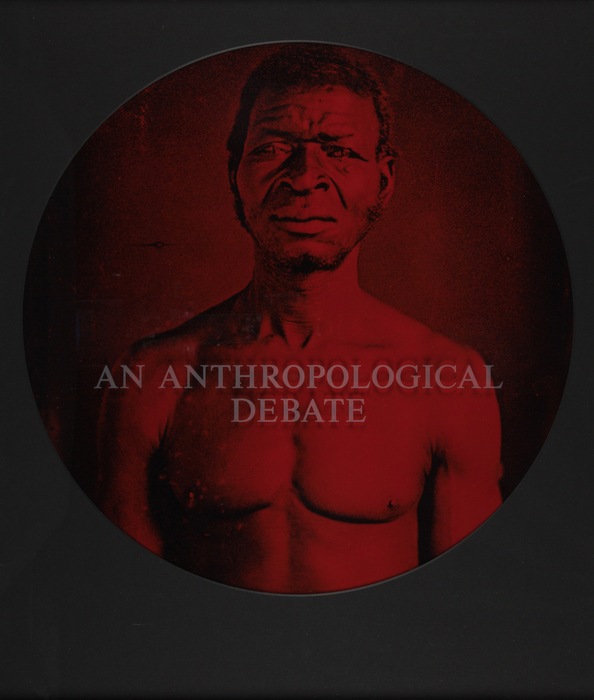

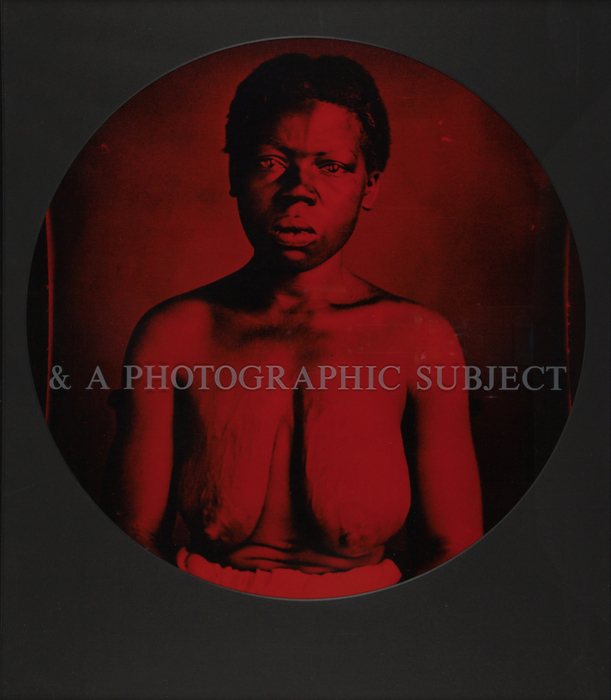

The ubiquity and relative affordability of photography have drastically expanded access to self-representation. Commissioned portraits let sitters determine how they are seen, as well as fundamentally affirm their existence and significance. But all images of people raise issues about power and agency. What are the relationships between the photographer, the person being photographed, and the intended audience for the image? What happens when a subject loses control over his or her representation because of the context in which it is presented?

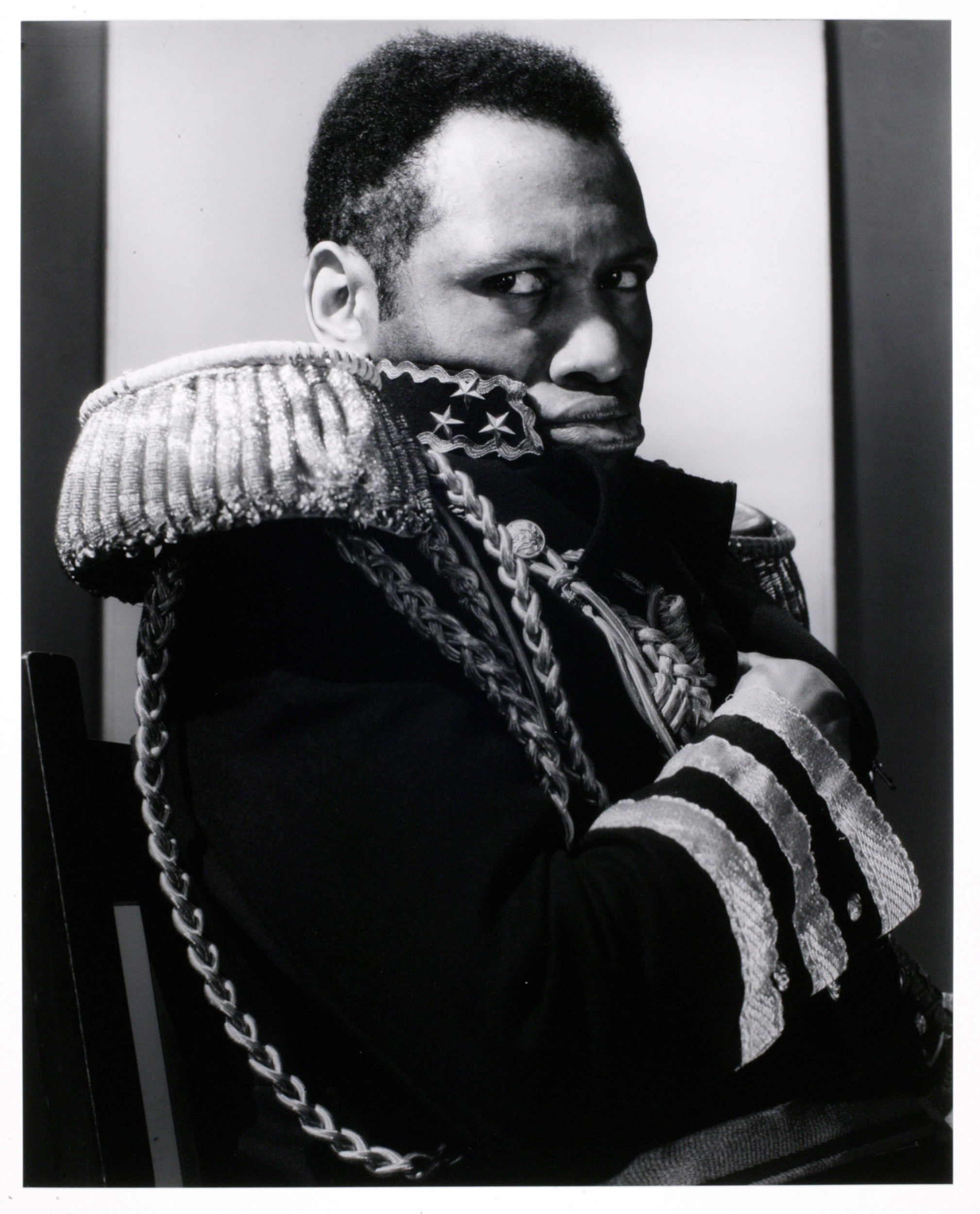

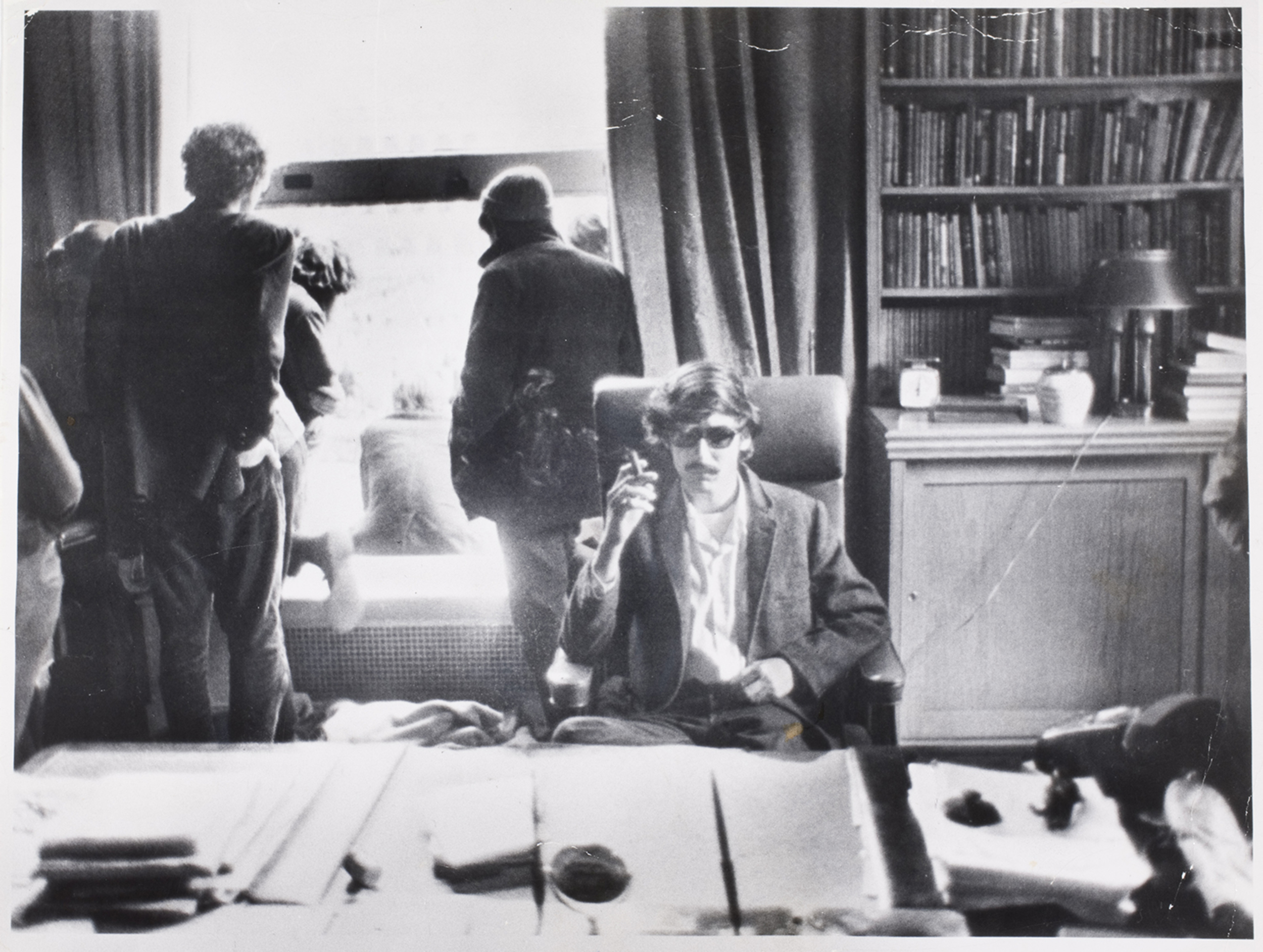

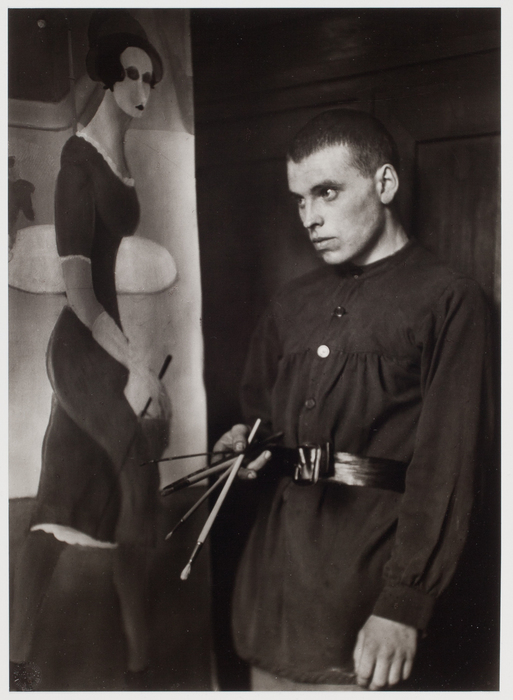

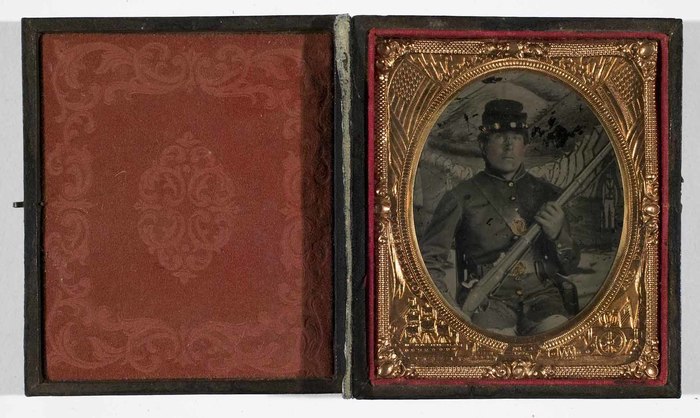

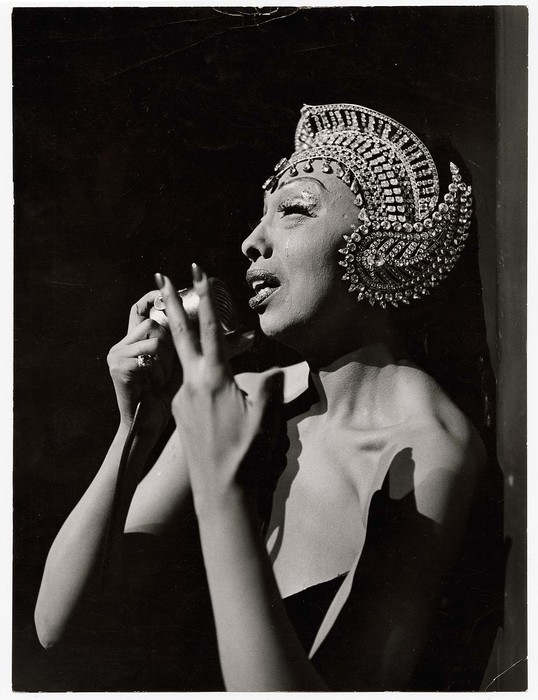

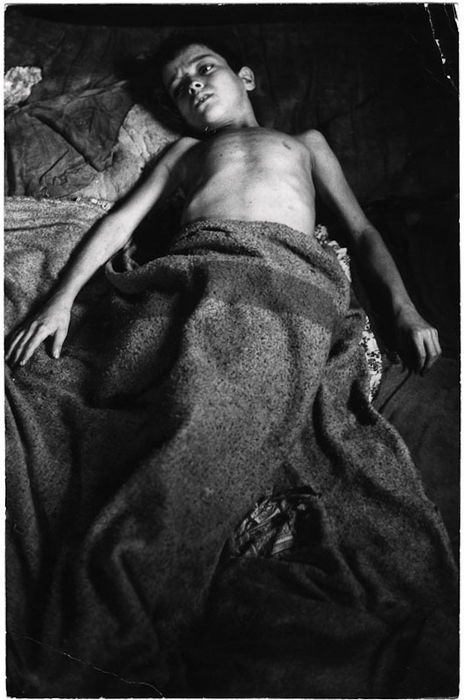

Drawn from ICP’s permanent collection, these photographs explore the ways in which portraits have been made and used from the nineteenth century to the present. Occupational and family portraits record a sitter’s relationship within a group. Celebrities and self-portraitists often exert the most control over their representations. In many images of war and social change, photographers choose subjects that reinforce their views. In collaborative portraits, people find ways to represent themselves as they wish to be seen, either in the studio or by seizing the moment through direct interaction with the photographer. Although the deceased have no say in their final representations, photographers have generally created dignified images that memorialize the dead and play a role in grieving. While each portrait serves a different purpose, each offers the opportunity to investigate the ways in which photography shapes our ideas about individual and collective identities. - Erin Barnett and Claartje van Dijk

The ubiquity and relative affordability of photography have drastically expanded access to self-representation. Commissioned portraits let sitters determine how they are seen, as well as fundamentally affirm their existence and significance. But all images of people raise issues about power and agency. What are the relationships between the photographer, the person being photographed, and the intended audience for the image? What happens when a subject loses control over his or her representation because of the context in which it is presented?

Drawn from ICP’s permanent collection, these photographs explore the ways in which portraits have been made and used from the nineteenth century to the present. Occupational and family portraits record a sitter’s relationship within a group. Celebrities and self-portraitists often exert the most control over their representations. In many images of war and social change, photographers choose subjects that reinforce their views. In collaborative portraits, people find ways to represent themselves as they wish to be seen, either in the studio or by seizing the moment through direct interaction with the photographer. Although the deceased have no say in their final representations, photographers have generally created dignified images that memorialize the dead and play a role in grieving. While each portrait serves a different purpose, each offers the opportunity to investigate the ways in which photography shapes our ideas about individual and collective identities. - Erin Barnett and Claartje van Dijk